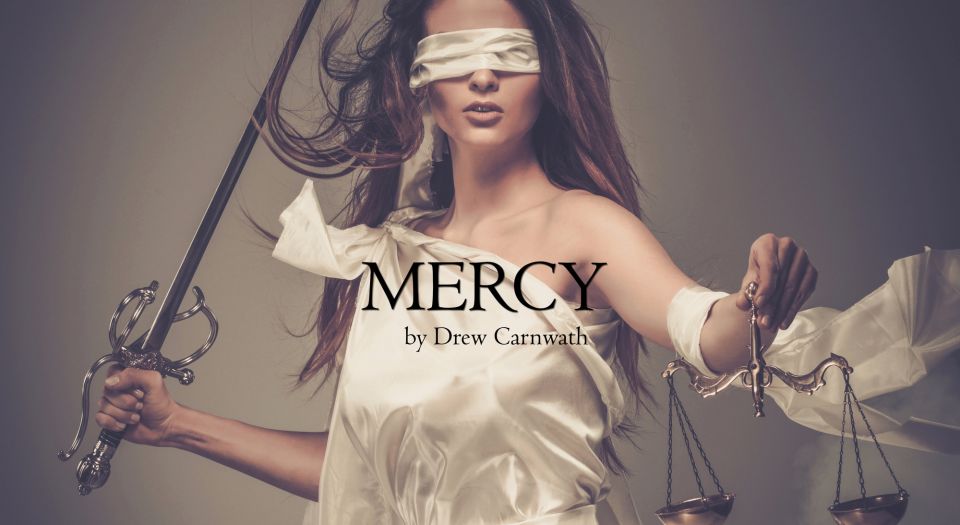

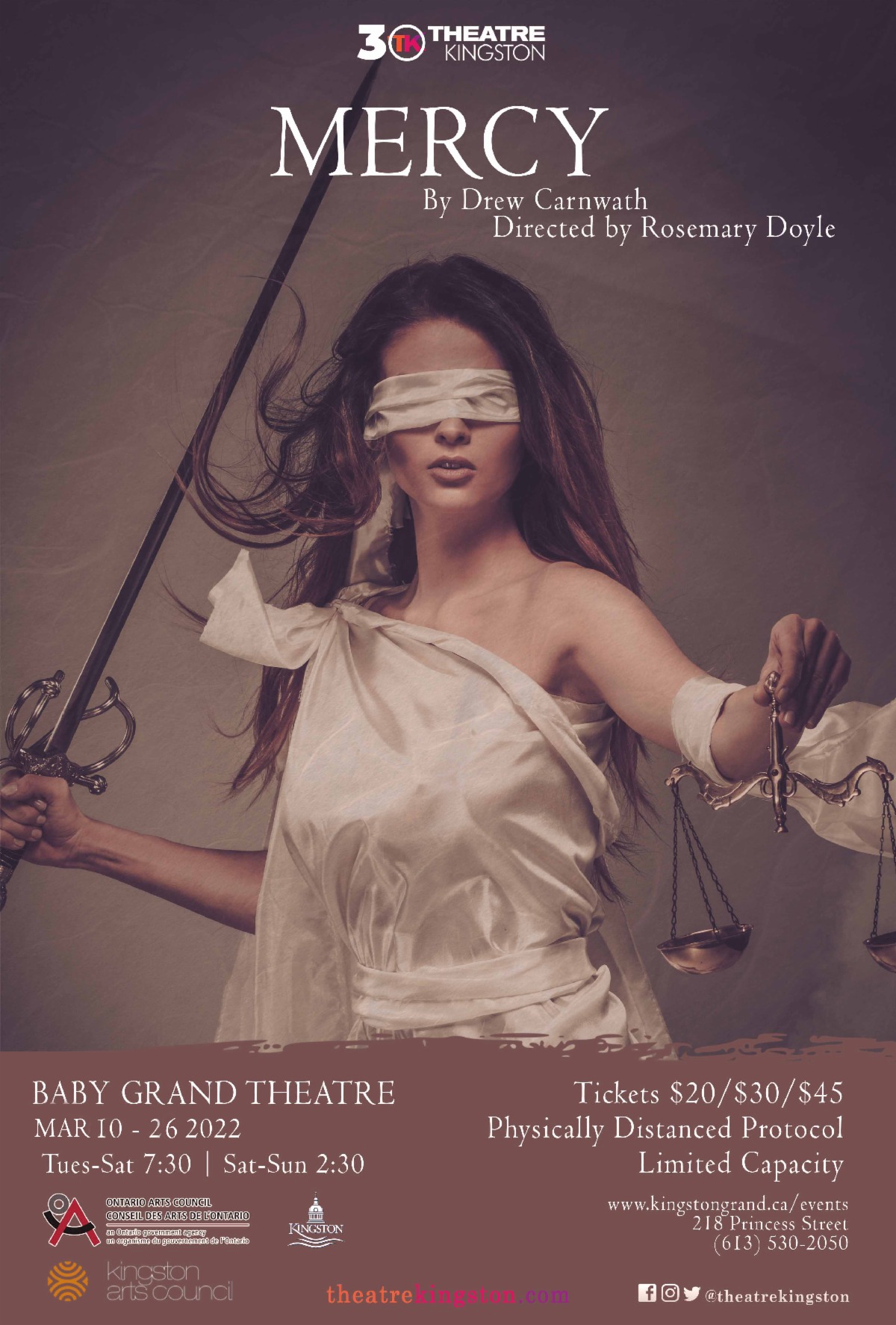

Words from the playwright of Mercy

DREW CARNWATH – The inspiration to write this play, specifically, was a desire to write a drama (albeit with some laughs, if I’ve done my work) featuring two strong women from very different worlds, who spend the majority of the action squaring off in a battle of wills, wit, and intelligence. They both want something from the other. They both make massive assumptions about the other. And, at different points in the play, they are both forced to compromise their most core values and beliefs. It won’t be an easy victory for whoever emerges the winner.

It’s important to note that I wrote Mercy, not in the immediate aftermath of the #MeToo movement, but about 18 months after the first wave of awareness and support and necessary conversation and revelations. If there is such a thing as Second Wave Feminism, I would say Mercy was written in the second wave of #MeToo-ism: it’s not a play about the effects of toxic masculinity or male violence specifically, but both of those ugly truths are present thematically.

Jordan and Katherine are strong-minded, fiercely intelligent, and they are both used to getting what they want. They are not just successful in their chosen professions, they are successful women in their fields. However, I would argue they are both defined and trapped by structures created by men. Put bluntly, they are both victims of powerful and insidious patriarchy, although they’d never admit to that at first. By the end of the play, however, after the power game of cat-and-mouse is all but played out, Jordan and Katherine realize they have more in common than they’d ever imagine. They share a kind of victimhood. As a high-end prostitute, Katherine is arguably in one of the most female of professions, albeit one defined by sex and power. As a lawyer, Jordan is succeeding in a man’s world, but the fact of her being female still holds her back from making partner in her firm.

Finally, if Mercy is about anything, it is about performance and role-playing in court, in bed, and on stage. It is only when we stop the role-playing, put down the masks and the armour, that we can truly see ourselves in others. To admit to weakness is the ultimate show of strength except it is no show at all: it’s us at our most authentic.