Escaping escapism – Studio 013’s ‘Cranz and Bernardo’

WARNING: This review contains spoilers and mentions of abuse and violence.

When imparting wisdom to new critics, I always assert that it’s ok if they see something they don’t “get”. Stick with the trouble. Stay rooted in your experience.

Since Cranz and Bernardo, the trouble has stuck with me.

Studio 013 returns to Theatre Kingston’s Storefront Fringe, supported in part by the Kick & Push Festival, with their misguided attempt at existential absurdity created and directed by Tyler Mathews. Although Cranz and Bernardo goes places, and with fervour, it does so in no specific direction.

Trapped in the liminal space of a cardboard box are two men who yell at each other for an hour. We meet Cranz (Douglas Connors) and Bernardo (Jordan Prentice) on the last day of their lives, unless they’re able to answer the mysterious algorithm they’ve been trying to solve for the last 499 days. But because the audience is never presented the algorithm, we don’t know what they’re trying to answer.

What we do see scribbled on the walls is what we come to understand as Bernardo’s attempts at cracking the code, slipping further into insanity as a result of Cranz’s physical and emotional abuse, and you know, the general hardship of being locked in a box for 500 days. A last ‘Hail Mary’, Bernardo retreats into his mind and tries his best to fill in the blanks of his memories and markings.

When the audience is first introduced to Cranz and Bernardo, their temperaments are opposite to when they first meet each other. In their world, Bernardo enters their predicament as this eloquent mathematician, while Cranz is just a feral dude who doesn’t want to be there. Any suspicions that they increasingly take on elements of each others’ personalities over time are quickly proven otherwise. The show also starts with a monologue from Cranz lamenting the loss of a son in a house fire, and because it’s never clear how they ended up in this place together, it seems Cranz—perhaps consumed by guilt or grief—tries to make a son out of Bernardo in a psychological Frankenstein way, which might’ve explained Bernardo’s child-like mannerisms (also incorrect).

Turns out, Cranz actually tried to set Bernardo on fire but has a last minute change of heart, to which I say, “Sir, you are in a cardboard box which (like Bernardo) is highly flammable. There’s also no way a small canteen would be able to extinguish the flames the size of a man doused in gasoline.”

The guidelines and materials they are provided with don’t even correlate to the algorithm, let alone, the actual solution that Bernardo apparently comes to. The rules include directions that they can’t both be sitting on the ground at the same time for more than five minutes, which reflects more of a sociological experiment than a mathematical dilemma (and was completely ignored in the blocking). They’re initially provided with the aforementioned gasoline and matches, along with some fruit, a bottle of champagne, and a tablecloth. Whether or not they were meant to be part of the puzzle, a deterrent, or simply sustenance, is unknown.

As the stakes of the story are prioritized over the mechanics of worldbuilding or character, the only investment the audience feels is out of obligation. And the way the audience is overstimulated deprives them of the ability to immerse themselves in the experience, no matter how hard they try.

The performance itself was powering, but not exactly powerful. There was so much yelling throughout the entire show, that it was physically painful to watch. Connors and Prentice whole-heartedly reflect a sense of risk and tension, but because they start the play at 100, there’s nowhere else to take it. I do commend their abilities to commit to their characters, because wherever they went, they went all the way.

Watching Cranz and Bernardo fill their time telling stories, hosting pretend dinner parties, and doing a lil’ song and dance was a cool way of using different modes of performance in order to twist how the narrative is conveyed. It was those moments I felt I was receiving the most authentic versions of the characters and performers themselves—a playful retreat from the gravity of the task at hand.

All intensity and no tension, Connors expressed who Cranz was rather than embodying him. His strong impulses were regrettably rushed, and the interiority his character calls for was met with excessive emotion which accelerated without a destination.

By nature of Bernardo’s character arc, Prentice had the opportunity to explore his performance in a way Connors might not have with Cranz. There was a sense of play in the ways he explored the character, however, many of his choices only worked for himself. The scope of what Prentice sought to incorporate led to an inconsistency in each of his characterizations. Bernardo’s brain damage is manifested as an infantile brattiness which has problematic connotations; his intelligence is reflected as a bad British accent which he slips in and out of; and at one point, he chokes on his own blood in the direction of the front row—which could add a sensory edge to the experience…

BUT IT’S COVID! Maybe if your audience is already paying $20 dollars to attend your show and braving a pandemic to support your work, don’t cough on them? That’s a pretty simple ask, right?

Bernardo is also supposed to be chained to the ground for the duration of the performance, and had the set piece he was attached to not broken off early on, it would’ve been such a visceral image. Prentice did try to casually fix this, but a stronger choice for Bernardo would be to walk around the box, swinging his chain in hand. Shackled but not tethered, Bernardo still carries the ease that Cranz lacks, further reflecting his feelings of constraint as a result of Cranz’ jealousy and paranoia.

Cranz and Bernardo lacked nuance because the performers kept performing the rage, violence, and depravity the script called for without having an actual understanding of where these emotions came from, or should be placed. The play doesn’t give you a reason as to why the two men act the way they do until you meet Doom, who’s double-edged clues are the only thing that necessitate a motive out of their final actions.

Periodically, a white face with blacked out eyes and teeth flashes through a hole Cranz punched through the box in a feat of anger. Doom (Nathan Yee) is an omniscient shit-disturber who revels in provoking Cranz and Bernardo by emotionally misguiding them to distrust their instincts and each other. Yee is a performer with incredible range, playing with every tool he had on hand. Entertained and evil, he twists that calculated corruption into comedy, making it clear he understood what his character asked for and how to convey that—and I’m not just saying this because he wasn’t screaming.

The performer carried Doom rather than letting the character carry him. Being a figure of despair and mischief, Doom doesn’t have to bogged down by any of the issues that Cranz and Bernardo are dealing with. Perhaps that offers the actor more room to play with what he can. Still, Yee was a face in a wall for maybe 15 minutes at the end of the play and the most captivating part of the whole performance.

Notably, the set was outstanding. I love how we were invited into the space with a world that EXPLODED past the stage. Cardboard scraps decorated the entire back wall and floor, although a stronger sense of entrapment could be achieved if the wings were covered as well. Unfortunately, the rest of the production design only haphazardly works in tandem with the performance.

Because every scene was punctuated by total darkness, the tension that was building would just be cut completely, so a cohesive atmosphere was never achieved. You’re taken out of the experience every time it happens and it was a choice that did a disservice to the performers who worked hard to heighten the drama. As a recording rather than the actor’s actual voice, Bernardo’s announcements fails to keep the audience engaged in the way one might hope during the blackouts. Being able to watch one moment fall into the next would be better depict the way Bernardo’s days have blurred together, and the disorienting fragmentation of his memories could be reflected using strobe lights. The tension and unease the story calls for never finds its footing because the play’s direction lacks attention to detail.

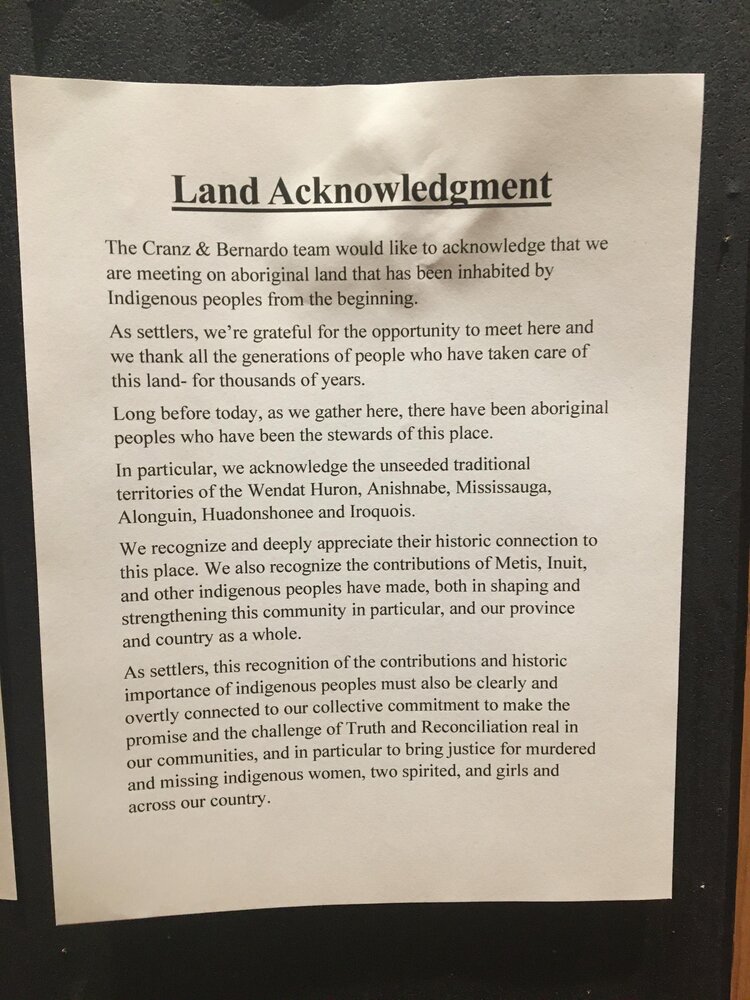

Studio 013’s land acknowledgement which misspells and misidentifies several Indigenous communities and fails to outline their positionality as settlers (or seek reconciliation or decolonization) in a meaningful way.

Cranz and Bernardo feels rooted in this toxic masturbation of masculinity where the will to power is rooted in a response or desire to dominate with violence and vengeance. Like the circumstances of Lord of the Flies, those instincts are so specific to the world of white, middle/upper class men. The bulk of their conflict stems from this misplaced understanding of significance, power, and respect they all carry.

As both the playwright and director of the production, there’s no guarantee what makes sense in Mathews’ head can be translated for another when there’s no external input. And as the head of Studio 013 himself, nothing stands in the way of this absolute artistic reign.

The way the show is written feels as if Cranz and Bernardo are acting out what Mathews understands as the answer to Doom’s question, “Who survives at rock bottom?” And Cranz makes it out alive because he’s (for lack of better words) the worst. The original algorithm is rendered futile since the circumstances of their escape are now boiled down to Mathew’s proposal of “human nature”. The production itself enables that ideology—that that is how you get out of rock bottom, that is how you survive. If you’re not saving your own skin, you’re doomed. I don’t even think most men in Cranz and Bernardo’s situation would act the way these men did, and since we’re never proposed an alternative, we’re just supposed to accept it.

Yes, if you look at the past 500 years of human history, only four of them have not been spent in some kind of global conflict. The thing about survival is that humans didn’t survive by being completely selfish, or abusive, or violent, but because time and time again, we collaborated. And Cranz and Bernardo is preoccupied with the horror, rather than beauty, of human instinct. It was a story that wanted to be told without the thought of how it should be told. The way the play seeks to unsettle and disorient lacks intention, so harm is only presented and never understood—an ultimately careless choice which extends to their poor excuse of a land acknowledgement.

When dust is thrown in the air but never settles, you’re too busy coughing to have an existential crisis.

Maybe the play itself is the complex algorithm that we’re not meant to solve. Maybe I already arrived at the solution, and overlooked it. Maybe the purpose is the excruciating pain of trying to figure out an answer that might not exist, but that is an unfortunate by-product rather than an explicit intention of the show. Cranz and Bernardo didn’t contribute or change what I came into the theatre with, and it didn’t give me anything to leave with either.

With theatre of the absurd, the lack of a solution is the solution. Ultimately, there is a relief to be found. But since we’re unclear what we’re meant to question, or be at a loss for, there is no liberation.

At least not until curtain closing.

Studio 013’s Cranz and Bernardo ran from August 5-9 2021 and is available on demand through Theatre Kingston’s Storefront Fringe, supported in part by the Kick & Push Festival. Click here for tickets and more information.