Music as a lifeline – ‘Beneath Springhill’ at the Six Feet Festival

No one knows what gets them through hard times until they’re in them.

And what our collective resurfacing in lieu of relaxed provincial health restrictions has prompted is a renewed empathy to an experience of unexpected entrapment.

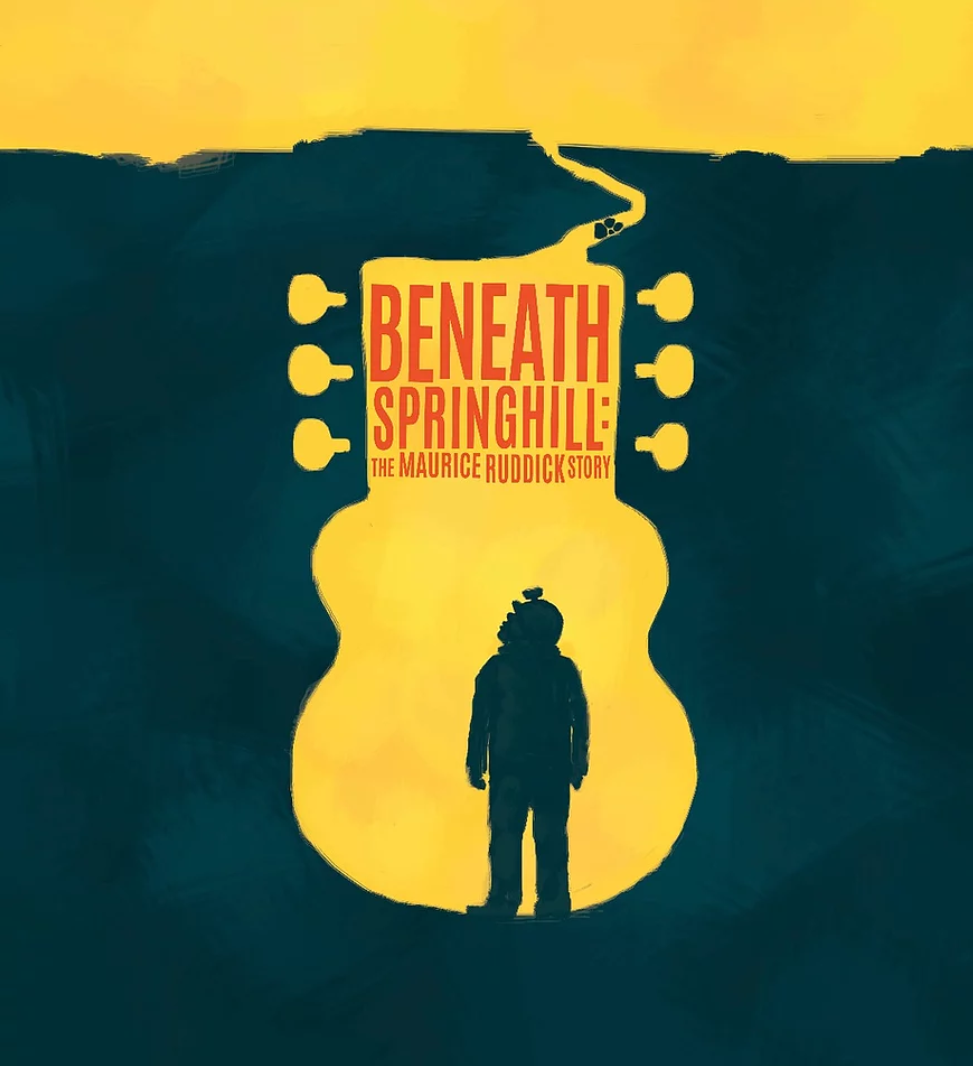

Created and performed by Beau Dixon, Beneath Springhill: The Maurice Ruddick Story follows the story of Maurice Ruddick (or “the singing miner”), an African-Canadian who survived the 1958 mining disaster when an underground earthquake hit Springhill, Nova Scotia. Originally premiering at the Thousand Islands Playhouse, this multi-award-winning play (directed by Linda Kash) now marks the return of the Festival Players’ Six Feet Festival at the Eddie Hotel & Farm’s BMO Pavilion.

What Beneath Springhill celebrates is the lengths we can go to support each other and create light when we cannot find it. Above or below, Maurice always understood music as his lifeline. Once an aspiring musician, he became a miner in order to provide for his wife and family of 12 children. Singing his way into love and fatherhood, and now out of survival, his voice and vivacity boosts morale long enough to keep his comrades alive until rescue.

The original music itself (Rob Fortin and Susan Newman) adds to the story, but not necessarily the overall experience. The richness of the drama alone is enough to divert your attention if nothing else is as engaging. And from the moment Dixon crawls and coughs onstage, we’re delivered to the heart of the play’s emotional intensity.

A solo performance, Dixon seamlessly embodies a wide range of Springhill’s community members equally devasted by the disaster. He transforms from a trembling and nervous Norma Ruddick, Maurice’s wife, collapsing onstage into the man underground. Maurice’s story is understood through a variety of perspectives—an insight on his life, and not just the fact that he might lose it.

Catastrophe doesn’t need to be represented because it’s felt. With minimal props and set, this production lends itself to imagination (almost as if Maurice was half-way to an afterlife). Additional ornamentation would’ve obstructed Dixon’s refined characterization and narrative, however, the sound and lighting design served to embellish both the stage and story. The environmental storytelling became more surreal as the sun set, the onset darkness immersing us further into notions of uncertainty and resolve—a moment unique to Beneath Springhill’s first outdoor production.

Even the camera’s capture of the performance is dynamic, breathing in and out of the evening’s events. The filming is able to emphasize Dixon’s capacity for storytelling by visually focusing on the performer at critical moment—minimizing flat air from the audience and empty space onstage.

A magazine clipping from LIFE Magazine’s December 1958 edition detailing Maurice Ruddick’s segregation at Jekyll Island where the Governor of Georgia invited the Springhill survivors.

Following the group’s rescue, the Governor of Georgia Martin Griffin invited the survivors to a week of southern hospitality at the luxurious Jekyll Island resort. But upon discovering that one of the minors was black, the governor insisted Ruddick be segregated from the rest of the vacationers—sleeping in separate areas and attending separate ceremonies. Although the other miners were reluctant to attend, Maurice eventually agrees to go on those terms because, after the almost-dying ordeal, they all needed it.

The racial tension Beneath Springhill touches on feels like an afterthought—a footnote at the end of play that’s quickly summed up within a couple lines. There’s a benefit that the audience doesn’t receive blackness as a death sentence (that’s the collapsed mine!), but the utter disrespect Maurice puts up with as a result of racism is written off as collateral damage. It does the character a disservice to boil them down to their marginality, but also to sweep it under the rug.

The talent and chemistry between the collaborators of Beneath Springhill have stood the test of time, space, and a pandemic. Livestreamed or in-person, nothing fails the production. This play brilliantly illustrates the hurt and healing of a community that’s been unexpectedly turned upside down.

Beneath Springhill: The Maurice Ruddick Story was apart of the Festival Players’ Six Feet Festival from July 19-31, 2021 at the Eddie Hotel & Farm’s BMO Pavilion. The play is also available for streaming here.