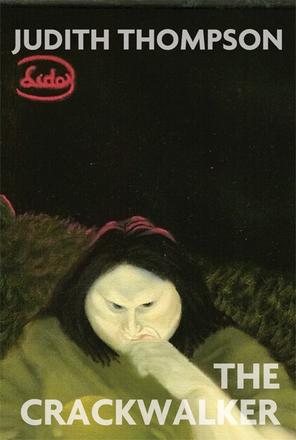

Script Suggestions I: ‘The Crackwalker’ by Judith Thompson

Welcome to the first in a new series of articles I will be writing for the KTA in which I discuss play scripts that might be of interest to our readers. This series is born out of a personal passion for reading plays. I have a shelf with over 500 titles sitting in my living room, a shelf which I regularly add to and take from to indulge my theatre cravings when I might not have the opportunity to catch another show. I have recently moved away from Kingston, but luckily for you, the blog had this idea for a series that allows me to provide my thoughts from afar. I would like to mention that because I am writing about scripts that were published years ago, scripts that also happen to be by authors who have no knowledge they will be receiving a book review suddenly, I am still venturing to provide criticism, but primarily aiming to introduce you to scripts I already have an interest in, so expect these to be less “Book Reviews” and more so “Script Suggestions.”

Warning: This article contains some spoilers for The Crackwalker. This article also contains reference to Substance Use, Child Abuse, Systemic Neglect, Sexual Assault, Domestic Violence, and Mental Illness.

Kingston is a rather strange city, if you go two blocks in any direction you seem to be entering an entirely different community. I moved to Kingston to attend Queen’s University, and it was months before I discovered anything beyond the campus. There is something endearing about how you can wander from community to community and instantly see the different lifestyles that each represents. Those who have never lived here likely know it as a University town, or a prison town, or perhaps they just recognize it as our country’s first capital. There are a multitude of identities to which Kingston can comfortably adapt, and we have a tight knit but active arts community, so one can only imagine many plays use the Limestone City as their setting. However in the Canadian theatrical canon, only one script jumps to my mind when I think of pieces set in Kingston, and that script is The Crackwalker by Judith Thompson.

The Crackwalker is one of the most difficult scripts I have ever had the pleasure of reading. It sheds light on the lives of the “permanently unemployable” (Thompson IV). The copy I own includes an introduction by Thompson titled “The Crackwalker Thirty Years Later,” in which Thompson discusses how the characters flowed out of her, and how the climax was never what she had intended to write about, but rather a true story that happened to make its way into the play (III-V). The climax is not the only event based in reality, as the characters are also heavily inspired by Thompson’s time working as a waitress at Nikos Deli, and especially by her time with the Ministry of Community and Social Services where she “…taught a motley crew of enchanting hard-luck characters that underwear went in the drawer, not the freezer, and that Coke and chips was not a healthy dinner, and that it was not cool to pull a knife on someone because they took a drag off your cigarette” (III, IV).

Now, I’ve avoided actually explaining what the climax is, but because Thompson discusses it in the introduction, I find it a fitting subject to address. If you don’t wish to have it spoiled, skip the remainder of this paragraph (and skip the introduction when you pick up the script). The play features an infant being murdered by strangulation. The murder is not intended as a malicious act by the character, and perhaps knowing it is done by someone honestly wanting the best for their child is the most disturbing part. Thompson mentions in the introduction that the act had originally taken place onstage, but she later realized it was just as impactful when it takes place out of the audience’s view, saying “When I became a mother it became clear to me that to see Alan strangle his baby would be unholy; nobody should see such a thing. We know that it happens, but to actually see it offends so deeply, so profoundly, that the viewer may never recover” (V).

Without a doubt, The Crackwalker is the most shocking script I have ever read (The only other script that might come close is Saved by Edward Bond, which similarly features the murder of an infant, however that murder is slightly more theatricalized and so does not quite have as potent an impact as Thompson’s work). The single scene’s writing alone might be enough to earn the title of most shocking, but the knowledge this event is one Thompson actually heard about from a woman she worked with, as well as the rhythm and poetry present in the characters’ dialogue throughout, make it a raw and authentic moment that appalls me yet demands to be told. As a reader who lives in Kingston, the most difficult aspect of The Crackwalker is the feeling of having met and crossed paths with these characters before.

Reading the piece, a long-forgotten memory was summoned from the depths of my mind. The first time I stayed downtown a hint too late, I was dropping off my now partner at their apartment. I went to leave through the parking garage, opened the door to the exit stairwell, and was met with a man hunched on the ground in the stairwell. He suddenly turned to me and screamed “Don’t touch my son’s milk!” There was no child around, nor did I see any milk. I was a bit shaken the rest of that night, but ultimately forgot the encounter until reading this play. The Crackwalker soars past the city’s striking limestone exterior to hone in on these discarded souls. Each of the characters are people you might have met, perhaps even spoken with, but most assuredly have passed by.

Thompson’s life experience and capacity for visceral poetry is the perfect vessel for capturing Kingston’s social fragmentation. She shows us characters who have been discarded by the government and dismissed by the upper and middle classes, but who want the same things as those who brush them aside. The show consists of two couples; Theresa with Alan, and Sandy with Joe. The story mostly follows Theresa and her relationship with Alan, with Theresa seeming to look up to Sandy, and Alan looking up to Joe.

The show opens by introducing us to Theresa, with scene two introducing Sandy. Theresa hopes to stay on Sandy’s couch for a while, but Sandy hears that Theresa had slept with her husband, and calls her out on it (6-7). The two fight for a moment but quickly reconcile when Theresa lies that “…he say he gonna kill me if I don’t shut up so I be quiet and he done it, he screw me” (8). Later in the same scene, Alan and Joe enter with a stolen motorbike; Sandy confronts Joe on allegedly raping her friend, he denies it and the truth comes out, causing Theresa and Alan to promptly leave (24-25). Scene three sees Joe and Sandy continuing to fight, with Joe aggressively grabbing Sandy and throwing her to the ground, giving us a small glimpse at their troubled domestic situation (25-26). The argument is cut short by Sandy collapsing due to a stomach seizure, during which the two make up and Sandy strips at Joe’s instruction, with hopes of engaging with him sexually (27-28).

These scenes set the tone for the entire show, every moment seeming to shift suddenly between arguments and abuse to sex and adoration. This volatility becomes a persistent rhythm – a pendulum constantly swinging from tenderness to violence, from love to neglect. The characters are too complicated and well-rounded to ever become easily defined as a victim, a villain, or a criminal. Instead, Thompson presents detailed portraits of human beings shaped by mental illness, poverty, and systemic neglect. Chaos is normal, intimacy and danger are almost indistinguishable, and the most beneficial life changing event the play sees is the opportunity to drive a taxi in Calgary.

The Canadian theatrical canon does not include many ventures into the rough streets of Kingston, and while The Crackwalker is not the Kingston I expected to see, it is a faithful mirror that absolutely demands to be held up. It is not just a compelling and difficult script, it is a call to action, or rather, to empathy, challenging us to see those we overlook and to ask the hard questions about how our community treats those we tend to ignore. I urge you to read The Crackwalker and sit in the discomfort, reflect on the Kingston that demands to be seen in this difficult text.

Thanks for reading, and keep an eye out for the next one… my shelf still has a few hundred scripts for us to look at, and while I am not venturing to cross off every title, I hope I can hold your attention for a few more.

If you would like to purchase a copy of ‘The Crackwalker’ by Judith Thompson for yourself, you can find the script published by Playwrights Canada Press here.

Thompson, Judith, The Crackwalker, Playwrights Canada Press, 2011.