Serving Good Sets, Script, and Perspective

“Write what you know. And what you don’t know, research.”

Playing the young and bold Tia, Makambe K Simamba speaks these words and thunder ripples across the darkened theatre. It is with power and conviction that she stares down her fictional screenwriting superior, and with a warning that finds relevance even outside the story world. Everyone is shaken with the implications.

This is my second time seeing a performance of Serving Elizabeth, and it is no less tense.

After catching this third installment of the Thousand Island Playhouse’s Fall 2021 season streamed online, I immediately called to see if in-person tickets were still available. From the dynamic and complex tension between the cast, to the seamless shifts in timelines, to the playwright Marcia Johnson also performing, I knew that this showing of Serving Elizabeth was something that would be worth seeing in person, even if it meant observing proper COVID ‘comportment’. After one waiting list, a committed box office attendant and a stroke of luck, I was on my way to seeing the show live.

The end result was nothing short of electric. Originally developed in 2017 as part of the Thousand Islands Playhouse’s Playrights’ Unit, Serving Elizabeth was a project that was born of frustration. Marcia Johnson, who in addition to being the creator plays the revolutionary matriarch Mercy and director Patricia, expresses this in her Playwright’s Note. She looks critically towards stories that are centered on ‘retelling’ history, namely The Crown, and tries to locate the voices that were lost along the way.

In her piece, Johnson paints two timelines: one in 1952 Kenya and the other sixty years later in the UK. With the action regularly shifting between the past and near-present, the relevance and conflict surrounding themes of colonialism, perspective, and leadership are illuminated in both timelines. Scenes in one time period send ripples into the next, comparable to intergenerational wealth or trauma. In writing this way, Johnson weaves a tight narrative that challenges not only history but also the way in which it is remembered.

While the cohesiveness of Johnson’s writing may be the product of four years of development, it was not alone in its notability. Rachel Forbes’ set and costume designs were equally well-constructed. Designing for one setting alone is a task—but for two, set 60 years apart and on different continents which work interchangeably? Now that is a feat!

Not only did Forbes’ stage effortlessly shift between the two time periods and through multiple locations, but through selective repetition, new dramaturgical meanings emerged. In the latter part of the play, a bar cart with expensive glass containers is brought on by Mercy, who is serving Princess Elizabeth (Shannon Currie), and stays on for the next scene, which takes place sixty years later in an expensive British mansion owned by Maurice (Andy Trithardt), an acclaimed screenwriter.

In the shared use of the cart, there is a question of power and privilege. Symbolizing wealth and class in both scenarios, the cart and other mirroring set pieces bind Elizabeth and Maurice in their ignorance, while uniting Mercy and Tia in their fight for justice amidst colonial mindsets. Parallels such as these offer new insights into the characters and exhibit the cleverness of the designer.

What also strikes me as significant regarding Serving Elizabeth is its placement in TIP’s Fall 2021 season. In my review for Back in ’59, I challenged the notion that a performance can only offer one thing to its audience (e.g. come and be happy, come and be challenged) and Serving Elizabeth comes as a direct response to that. In addition to enjoying the warm and comical moments onstage, audience members are asked to grapple with very real questions of power and perception. Regularly throughout the piece, the ‘goodness’ of Elizabeth or the monarchy in general were challenged, something that can be a heated discussion across demographics today.

Further expanding on this, the narrative brings forth very real history that audience members may be unfamiliar with. In both timelines, Jones uses Kenya’s history of the Mau Mau Uprising to shape her characters and Mercy’s rooted mistrust of the British. While I was more or less unversed in British colonialism in Kenya going into the performance, Serving Elizabeth casts out any ignorance of the atrocities committed against the Kenyan people, which included 90,000 executions, 160,000 people detained in atrocious conditions and trauma that still affects the country today.

While the restaging of this history sees Tia reconsidering what she knows about Kenyan and British relations, it does the same for the audience. Just as Elizabeth is made to listen to Mercy’s experiences and consider her non-neutral positionality, we are asked to watch, listen, and consider our own. I applaud Thousand Islands Playhouse for facilitating this development, and through staging it, asking these considerations of its audiences. Perhaps watching will see audience members challenging their own history, and as Tia suggests, doing their own research.

Overall, Serving Elizabeth offers a smart and vivacious tale that re-examines the telling of true events. Through her careful structuring, Johnson considers the subjectivity of history and challenges it in both the past and present tenses. With runs at Stratford Festival, Western Theatre and soon to be Belfry Theatre in BC, I hope that the piece keeps up with this challenge and continues ‘serving up’ its fresh perspective.

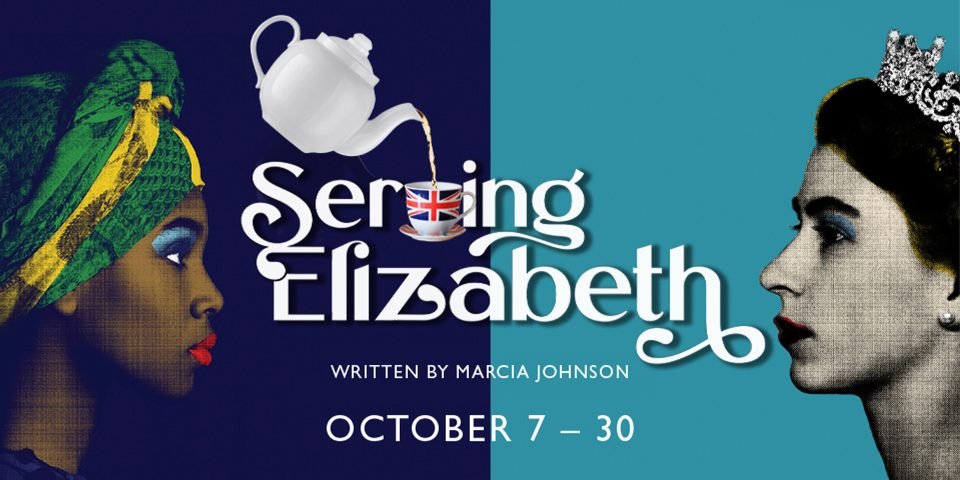

‘Serving Elizabeth’ ran at Thousand Islands Playhouse from October 7-30 with performances both live and streamed online. For more information on it’s upcoming run at Belfry Theatre, click here.