Getting Real with ‘Play: Dramaturgies of Participation’

What comes to mind when you think of audience participation? No, for real, tell me.

Don’t want to? Okay, I’ll go first. When I think of participation, the little sing-song voice in my head starts humming Al Simmons’ “Don’t Make Me Sing Along”. This tune was rattling around in my mind when I met with theatre scholars Dr. Jenn Stephenson and Mariah (Mo) Horner to talk about their research project, play/PLAY: dramaturgies of participation.

“Whenever I go to a musical show,

I’m driven to utter distraction,

For the actors today seem to act in a way

That necessitates crowd interaction.

Participatory theatrics!

I find them a horrible strain,

So as I take my seat, I always repeat

This old familiar refrain…”

— Al Simmons, “Don’t Make Me Sing Along”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Stephenson and Horner have been thinking about participatory theatre together for a long time. Since 2020, their blog play/PLAY has been an online presentation of their effort to collect, describe, and analyze participation in live performance. The blog includes posts from Stephenson, a professor in the DAN School of Drama and Music, and Horner, a PhD candidate in Cultural Studies at Queen’s. It also features entries from a diverse group of guest writers who reflect on their own theatregoing experiences.

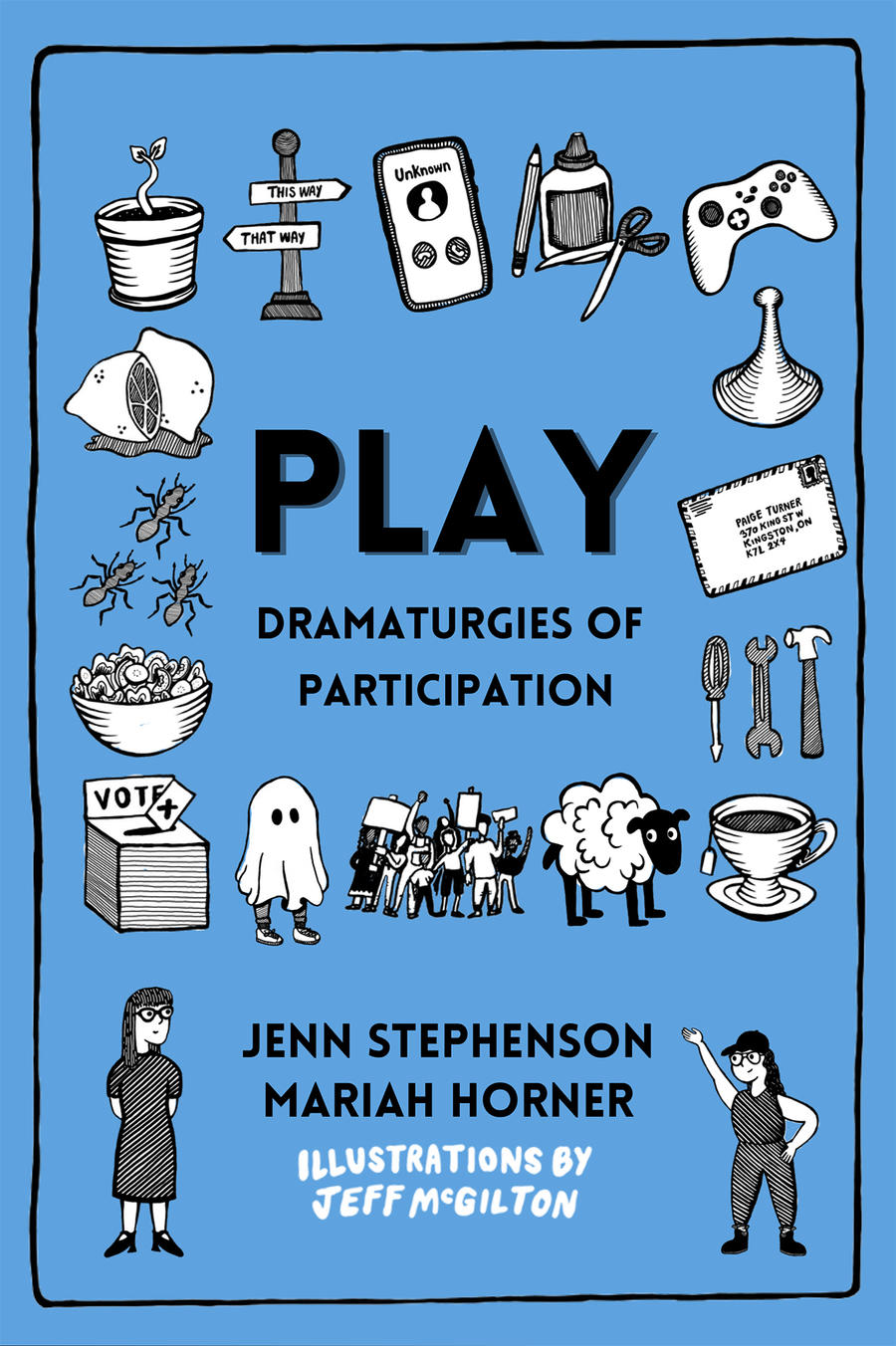

This research will soon find its way into a book, Play: Dramaturgies of Participation, which is set for publication in May with Playwrights Canada Press. The book features a series of standalone, alphabetical mini essays that explore live performances in which the audience becomes participants.

Stephenson and Horner are particularly interested in “upsurges of the real” in live performance. What does “real” mean in this context? “We think about ‘real’ in a very specific way, which is different from authenticity,” says Stephenson. “Specifically, realness is in opposition to being fictional. Characters live in fictional worlds. We live in the real world—or the actual world—and then what happens in participation, or when audiences get involved, is we cross over.

“How do I, a real person, talk to a character? And how does that work? Sometimes when audiences participate, we’re invited to step into the fiction and become a character. But we’re still always audiences. I can’t ever fully become a character, because I’m not an actor. That’s not my job.”

“The performer can act as an interlocutor between real and fiction,” Horner elaborates. “I think about that Kick & Push show from [2021], Roll Models.” Presented by the ArtFolk Collective, Roll Models combined theatre, improv, and the role-playing game Dungeons and Dragons. “[The actors] weren’t being real either, because they were acting as orcs. But we were playing a game that was transformed, live, in front of us. We were being real players playing the game, really rolling dice.”

Stephenson is interested in moments when the borders between the real and the fictional blur. “We talk about theatrical frame, and we also talk about magic circle, which is a game term for the same thing. If you step into the magic circle, then you’re doing game things that don’t count in the real world.”

Moving from performance to page, character and voice are major considerations. “Both of us are in this book,” Horner points out. “We refer to ourselves as ‘we’, and sometimes I’ll say, ‘Jenn’, but sometimes Jenn will say ‘me’. These roles as participant-watcher are delineated enough that they can become roles as participant-writer.”

“The stories in the book become really personal,” says Stephenson, “because it’s our bodies. We did the shows, we were there. We were asked for thoughts, and we were asked to contribute. We were asked to dance or sing or paddle canoes, or whatever it was, running around in the dark like maniacs… We did it. It’s really important that, as we were writing the book, it didn’t get too distant and too scholarly. We really do say, ‘I did this, and this is how I felt, and that was weird. And I was hungry. I was scared, I was confused.’”

“It’s stretching our academic voices,” says Horner. “As a writer, it’s such a gift to be able to take thinkers like Foucault or like Brecht, and to think about them as you’re running in the dark through the woods, you know, and really being able to hold both of those voices on equal footing.”

Participatory theatre can be vulnerable. “An audience member who is sitting in a theatre, in a red velvet chair in the dark, is pretty safe,” says Stephenson. “You’re not moving. Other people are not moving. The actors are over there, and they’re quite far away.” (“Keep the house lights low, I’m not in the show,” sings Al Simmons in my head.) “But then when you move into audience participation, you’ve crossed into the magic circle. The actors can be quite close to you. They’re talking to you, often directly, and asking you questions. Sometimes the actors are touching you.

“Sometimes there are peer to peer experiences, like in asses.masses, where the audience together as a group has to do something, or work together or figure something out. So relationality is a really important part of audience participation. How do we build those connections? And what do they mean? …And how do we agree? How do we consent? What does that mean? How do you know when things have gone too far?”

The book examines these ethical questions from multiple angles. “There’s an entry called ‘consent’,” says Stephenson. “There’s an entry about touching, there’s an entry about relationality. We have one about refusal, we have one called ‘opting out’—what happens when I need to walk away? What does that mean? What are the politics of not participating? How powerful is it to say no? There’s a great entry called ‘killjoy’, which is about interrupting other people’s fun… So that’s a really important part of it for us. Thinking about people in space and time together.”

Horner finds this theme, relationality, particularly exciting. “One of my favourite things about this book is that through this investigation of how we are together, and relationality, it’s led us towards a lot of Indigenous scholarship that we’re engaging with—Leanne Simpson, Dylan Robinson. There are a lot of scholars all over the book who are writing about, not just what it means to be humans together, but what that means in relation to the planet, in relation to the Anthropocene, in relation to sovereignty. This conversation that we have about refusal, we ended up pairing it with a larger conversation about sovereignty and refusal. All of a sudden, this dramaturgical technique can illuminate these larger questions that are really pressing in the zeitgeist right now. Specifically, how we are to each other in conflict, how we are to each other on the planet.”

With the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, people’s relationships to each other shifted drastically. “We started the book before the pandemic,” says Horner, “and we wrote through the pandemic. Obviously, participatory theatre changed. This pandemic ended up being extremely revealing for the core ideas of the book.”

Stephenson agrees. “Participation is always in relation to somebody else. How do you do that during COVID? Fortunately, the artists that we were interested in kept going, [and were] smart, creative, motivated, and responsive. They came up with such exciting new forms. COVID was a real catalyst for innovation in participation. And now we’re watching things kind of come out of that.”

The conversation turns to access. What if someone wants to participate partially? Or not at all? How does participatory theatre account for that? “Some of it does this really well,” says Stephenson, “and some of it does this really badly. A critical part of participation is the invitation. It’s when the show says to you: ‘Will you come with me?’” (“Everybody now!”)

“Some shows are not very accessible. Shows that are structured in such a way where you need to run, or you need to climb the stairs, or you need to walk through on uneven ground in the dark, or you need to eat or drink substances and you’re not really given an opportunity to refuse—I mean, obviously, you can refuse, but it’s difficult. It feels socially difficult.”

“We’ve started to grapple with, what does it mean when you feel like you’ve been backed into a corner? One of our entries is called ‘fascism’. One of the entries is called ‘complicity’—what happens when you do a thing because your character wants to do it, but you as an audience member kind of really don’t? And then the flip side is, because a lot of this stuff is one-on-one, or in very small groups, or really is directed to you as an individual, it’s very customizable. So some of the stuff is very, very unique. It’s a huge range of different kinds of ways that artists are grappling with this question of access.”

Playing researcher and participant at the same time can get complicated. “In order to do this research, we needed to participate,” says Stephenson. “But it also becomes a little complicated when you’re the researcher, because you’re trying to maximize your experience in certain ways. You’re trying to look behind the curtain—what happens if I go left instead of right?”

“It automatically makes a lot of space for positionality,” says Horner. “This brings me right back to the beginning of our conversation about realness. [Participatory theatre] automatically acknowledges the heterogeneous reality of your audiences.”

“We could not do this research without artists,” Stephenson adds. “Over the years, we’ve developed relationships with all the artists we write about… We work really hard at staying connected, keeping up with what’s going on… We try to keep up with things as they evolve. The artists have been so generous to us, and so amazing and brave. For artists to talk to scholars is kind of scary. And so they’ve just been so wonderful.”

“And so brilliant,” Horner emphasizes. “Really brilliant as a cohort… Listening to these artists write about their own stuff, and their own impulses—they’re all great writers and great thinkers. We ran this conference [Participatory Performance Summit] on Discord in April 2022, and it was great. These artists, these scholars, could just talk to each other forever. It was a great group. A lot of really brilliant ideas came out of it.”

Jenn Stephenson is Professor at Queen’s University in the DAN School of Drama and Music. She is the author of two books: ‘Insecurity: Perils and Products of Theatres of the Real’ (UTP, 2019) and ‘Performing Autobiography: Contemporary Canadian Drama’ (UTP, 2013). Recent articles have appeared in ‘Theatre Research in Canada’ and ‘Contemporary Theatre Review’.

Mariah (Mo) Horner is an artist and Ph.D. candidate at Queen’s University in the Cultural Studies Department. She won a 2022 Mayor’s Arts Award (Creator) in Kingston as a site-specific theatre artist and is a vocalist with Kingston supergroup The Gertrudes. Recent articles have appeared in ‘Canadian Theatre Review’ and ‘Theatre Research in Canada’.

‘Play: Dramaturgies of Participation’ is set for publication in May 2024 through Playwrights Canada Press. The book is available for preorder here.