Black History Movement and the Importance of Framing

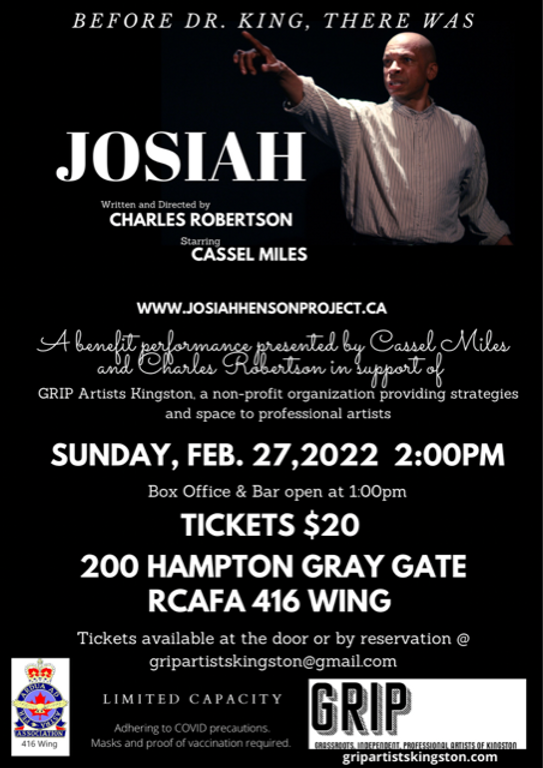

Alt text: The poster features a picture of Cassel Miles, a middle-aged Black man who is wearing a button-up, striped shirt. He points to the left and looks on with great purpose. The rest of the poster has information pertaining to the performance’s February 27th showing, including show time, price, and information about GRIP Kingston.

While some pieces of theatre find their footing in fiction, others find meaning and shape in the staging of true events. In the last stretch of this past Black History Month, an example of the latter came in the telling of an essential piece of American and Canadian Black history.

JOSIAH, co-created by director Charles Robertson and sole performer Cassel Miles, was a multi-disciplinary dip into the life of Josiah Henson, a Black American labourer and preacher who escaped slavery in 1830 and resettled in Canada. Although this run of JOSIAH only offered one performance, a Sunday matinee on February 27th, the project has a long history of its own, including a period of development in Kingston and touring across Ontario. The event served two purposes: to support the exploration of Black histories such as Henson’s, and to raise funds for Grassroots Independent Professional (GRIP) Artists Kingston, a local organization which advocates for artists in a number of ways, including providing spaces to work in.

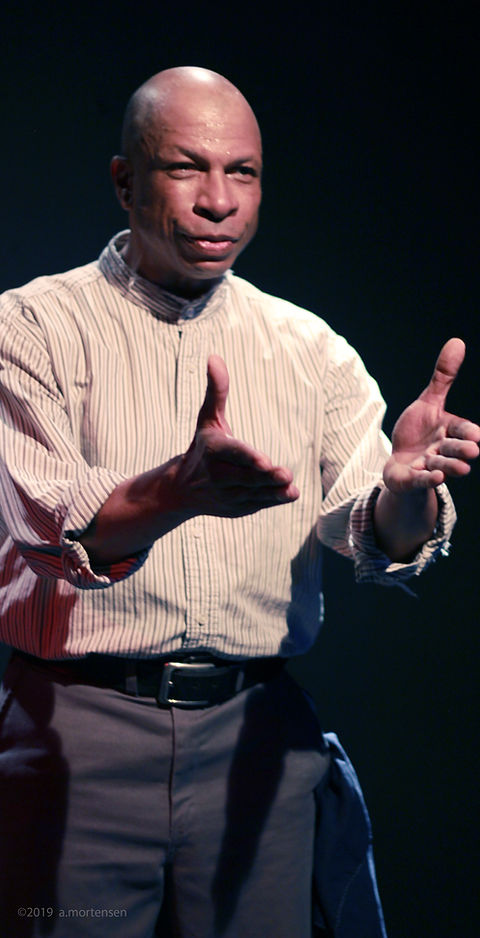

Alt text: The photo shows Miles in the same striped shirt with grey pants and a black belt. He has his hands pointed out away from his chest, palms upturned, and has a stern look on his face.

As it turned out, GRIP was the provider of space for much of the JOSIAH rehearsals, and as such, the team was looking to pay it back to the organization. They did this by donating all their proceeds and by staging the piece in the very room that they did a good portion of their rehearsals, which just so happened to be the Air Force Association of Canada (RCAFA), Wing 416. With a few added rows of chairs, two sets of lights, and a soundboard, the stage was set.

What followed was two and a half hours of Miles giving it his all. What was fascinating about his performance was not entirely the words he was saying, but how his body reacted when saying them. With each character he brought to life (and there were many), a distinct posture was taken, a unique intonation was formed. From the grasp of a bottle to the grip of a whip, the way he handled everyday items clarified who was speaking and provided insight into who they were.

Trained in dance, voice, and movement, Miles put his own touch into the most mundane and monstrous of activities, from his tip-tappity ploughing of the fields to a musicalized slave auction. With both humour and dread, he enacted some of the brutal realities of the transatlantic slave trade. Movement and music were used throughout the piece to achieve a number of different effects, including sailing downstream, riding a horse, or asking the audience to clap along and shout out ‘amen’. Through this merging of mediums, Miles allowed the audience to engage with the tragic and triumphant story of Henson on multiple levels.

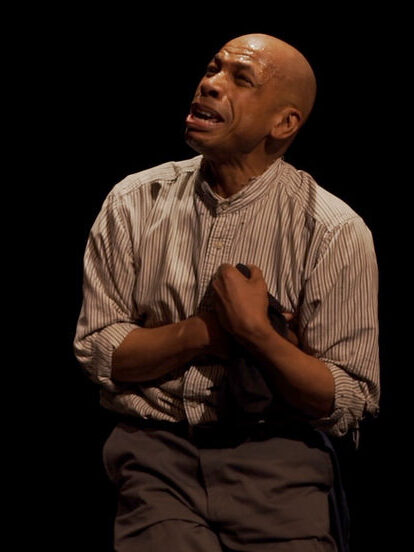

While I am glad to have had this engagement, I am hesitant as to how it was ultimately framed. The majority of the play’s makeup, informed by Henson’s multiple autobiographies, was detailing his ownership journey from master to master and his subjugation and subsequent rejection of the slave trade in the United States. It was only within the last 10 minutes of the play that he denounced his captors and escaped to Canada, with a gleam of hope for all that was to come.

Alt text: The photo shows Miles in the same striped shirt with grey pants and a black belt. His hands are clenched and covering his heart while his face is as if he were calling out in pain.

This made for a climax that certainly kept the audience hanging on until the last minute, but also gave the impression that systemic racism stopped at the border. History shows that Henson did make it into Canada, but four years before the country’s Slavery Abolition Act came into effect. At the same time, mission schools for Indigenous children (the blueprint of the Residential School System) had been operating in Canada for more than 200 years. While I am not intending to dim the victory of Henson’s liberation, I only hope to challenge the belief that, compared to the US, Canada doesn’t have any issues.

Further muddying the play’s ending, during a brief talkback featuring its two creators and GRIP Executive Director Vicki Hargreaves, Robertson mentioned that when in Canada, Henson went on to do some monumental things. This included the recruiting of local abolitionists to aid him in creating the Dawn Settlement, an essential organization that helped refugees who experienced enslavement gain education and skills pertaining to self-determination. How would the meaning of the play have differed if it ended with Josiah dealing with the realities of displacement, or featured him passing along that knowledge to others?

At the end of the talkback, Hargreaves mentioned that JOSIAH had recently been signed on for various performances at schools in the Kingston area. The creators rightfully thanked her for facilitating the spaces that allowed for their performance and its development to happen. There is no doubt that the students will benefit from seeing the performance, especially with Miles as their storyteller. However, in crafting the content or session that might serve as a debrief for the performance, what questions would they ask? What insight can JOSIAH offer its audiences into the complex and dubious nature of the transatlantic slave trade other than the fact that it happened?

Like Josiah’s story, the development of this play has been a journey; and one that is not yet over.