Making a Fairy Tale with Jesse H. Wabegijig

Jesse H. Wabegijig is one of the artists for the 2022 Kick & Push Indigenous residency.

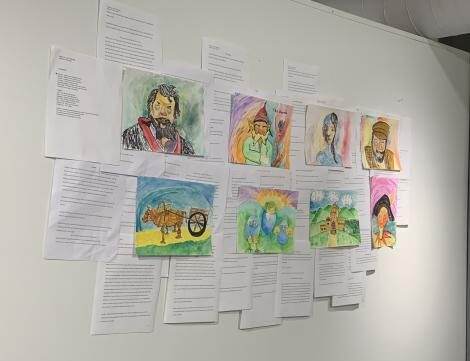

They spent the residency working on their new play, where Jesse was able to put together an installation that went up in the Tett Centre for creativity and learning. On the opening night of the installation I got the chance to speak to them about the time in the residency, and to hear a little more about their new work: Pictures at an Exhibition.

The conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

How are you doing today?

Ooh, today was busy. I had a few meetings this morning. I was in Toronto to begin with, then I came down on the 2pm train. I got here at about five, there was a delay, then I came into the studio and set everything up. So a little disjointed.

Could you tell me a little bit about your residency with the Kick & Push?

Yes, the residency with Kick and Push was originally supposed to take place on Cedar Island. However, for the time that I was contracted, the boat that was going to bring me there had broken down. Through a great deal of resilience, we set me up in the rehearsal hall on the second floor of Tett Centre. I worked there for the first day, and then we transitioned into this gallery where I continued my work for another three or four days.

What is the importance of Cedar Island for you?

Well, the initial reason why we wanted to work there, and why I was very interested in working there was that [Pictures at an Exhibition], is at its heart, a puppetry play. A puppet play that specifically utilizes a motif of light and darkness, and how it relates to Ukraine, addiction, drugs, and a few other plot points that exist within the script. To reflect that, I wanted the piece to be black and white when it begins, and I wanted to do that through shadow puppetry.

So what I was very excited about on Cedar Island was all of the natural light. Using fires and flashlights, developing the play from a place of disconnect from society, I thought that would be very nice, especially because all my characters are living in that way.

Can you tell me a little bit about your characters? Which one is your favourite one?

In Pictures at an Exhibition, my favorite character has to be the Gnome. Within the play, the Gnome acts as a sort of Prophet to the rest of the world. He knows bad things are going to happen, and he wants everybody to know. So he attempts to scare them off the path to Kyiv; he knows that there are going to be troubles along the way. That even when they arrive, not all will be as good as it seems.

Where do you want the piece to go? Past working with Kick and Push?

Past this residency, it continues its development at a sort of culture exchange group. We’re all going to be living out in Brampton for just under a week. While I’m there, we’re going to be exploring together what it sounds like to music. Music that is also based out of Eastern European traditions, which includes things like classical music, and some of the traditional songs from the Ukraine region. There’s a specific point in the script where Modest Mussorgsky starts a hymn to keep people going. This is a moment where I want to showcase the resiliency of a people that are going through what they are, and needing to move.

Are there times where you felt like you yourself needed to move? Some of the questions you have in the installation are about community and peace, have you yourself felt displaced at any time?

I mean, I am Indigenous. I come from two sides of residential school that produced people who have wildly different experiences. One of those being having a child when they’re 13, not knowing where they’re from, thinking they were white for most of their life. Another family member who was just devoid of parents because they kept him hidden from the residential school system. So he didn’t get a formal education. He didn’t get diagnosed for any of his mental disorders. He ended up having a number of children and a number of things happened. All of this happened because none of them knew where home was. They were deprived of their language, their culture, and most of what, they’re deprived of their family and community, which put them in a sense of war at themselves and everyone around them.

Thank you for sharing. Where do you find community? Where do you find home?

That’s funny. I have always struggled to find community amongst the reserve nation that I’m from. I’m ojibway from Wiikemikoong Anishnaabek Territory located on Manitoulin Island. And I’ve always faced a hard time feeling at home there. I’ve found community and hardship and really family amongst people who I don’t share commonality in race, nation, or origin.

What do you value in community? And what do you value within your found family?

Within community, it is important for there to be acceptance; acceptance in what we fail at, and acceptance in what we excel at. Within my own community, the one that I eventually found, that is what made me grow past a lot of the faults that I had within myself. Whether that be when I was younger, with alcohol, and other things. Once I found that [acceptance], none of that mattered to me anymore because I didn’t need to change myself to allow myself to be happy. I found that I – we all live in a very complicated world, and we all deserve happiness. We don’t necessarily need to change ourselves.

Are there any characters or any story plot points that really speak to you as a person and to us as your character?

The entire play is this fantastical fairy tale of Modest Mussorgsky, going from Russia and Ukraine, because of his obsession with the pictures and an exhibition, but along the way, he is forced to radically accept others into joining him and continuing on this journey. With each of these challenges, it was a chance to depict ways in which I myself have been accepted, and community, and ways that I have helped others be accepted into the same communities. There’s a point where there’s orphan children, they’re called the Tuileries. They are these nice little French children that ran away and decided to pretend to be an Italian banjo player, haunting the Russian countryside. It’s fantastical. Why would this be happening there?

The main point is that there are these orphans and we eventually find out that they gave up their names and they left their orphanage and they’re nameless. And they’re okay with being that until they’re accepted, and they’re given names, and then they have a home. It was important to me that they weren’t weren’t French names, that the characters were being given names within the nationality of the people that were accepting them.

I want to ask: what is important in a fairy tale?

Practical lessons. If you’d look at Brothers Grimm or more of the older fairy tales, they’re all very much like: “Don’t be an idiot!” They were kind of criticisms of the storybook definition of love and, like, radical love. But in these fairy tales it’s like, if you love this person and they start to hurt you, say no! They always have these like very poignant sort of parents that were worried about their children being hurt, so they decided to scare them. Within this, I wanted to capture that same essence of what I think a fairy tale is: all these radical stories of acceptance of others, of “The Other.” As this character, he shouldn’t really be in charge of anything, because he’s out of his mind drunk at the start of the play, and gets sober and more sober as the play progresses, he radically accepts people and builds this community that eventually is self-sufficient.

Would you say that this is Theatre for Young Audiences? Or is it for anyone?

It’s built like a theatre for young audiences, but it does not ignore the reality of what’s going on in Ukraine. The war is ever present in every part of life. I don’t try to pretend that it hasn’t happened. I also don’t try to pretend that it’s a fairy tale world where anti-semitism doesn’t exist or doesn’t have the conflict between Russians and Ukrainians. That’s something that is always present and always at the forefront of a lot of the scenes is that these people are dealing with these things. They are fantastical so they’re making radical choices, but they are still people.

What would your elevator pitch for the piece be?

“Pictures at an Exhibition follows Modest Mussorgsky as he travels from Russia to Ukraine, to witness the pictures at an exhibition. Pictures at the Exhibition is a celebration of life, joy, and radical acceptance within the communities.”

Jesse H. Wabegijig‘s Pictures of an Exhibition was on display in the Tett Centre during August 11-14.